Do you remember the childhood nursery rhyme, ‘What are little boys made of?’ The version I knew said they were made of ‘slugs and snails and puppy dogs’ tails’. It has been pointed out that this rhyme is unfair on boys, given that little girls are made of ‘sugar and spice and all things nice.’ But I think these are all awesome things which little boys should be proud to be made of. Puppy dogs’ tails are obviously great (as long as they are still attached to the puppy) but slugs and snails are even better. Let me take you on a beautiful, slimy journey through the world of slugs, and you will soon see.

Let me break it down for you

I recently added a compost bin to my garden, expecting worms to happily move in and start working through the rotting garden waste and vegetable peelings. But my bin’s most abundant inhabitants so far are enormous orange-fringed slugs.

It turns out that slugs are really important as they break down compost and other organic matter. Slugs break down their food using their rough, tongue-like radula which can have up to 27,000 teeth, depending on the species.

Different species have different diets, and despite being so universally disliked by gardeners, most slugs aren’t even interested in eating your salad. The leopard slug (Limax maximus) for example, feeds almost entirely on rotting material. And many of them don’t eat plants at all! Of the 44 species of slug in Britain 12% are carnivorous – their prey includes earthworms and even other slugs – and 17% are fungivores. So let’s learn to live with slugs, and maybe even love them, as Monty Don said in this recent episode of Gardeners World.

The episode featured ecologist and slug researcher Imogen Cavadino, whose enthusiasm for the slimy invertebrates is hard to resist. You can also watch an excellent presentation by Cavadino for the Field Studies Council: Slimy, Sticky and Unloved.

It’s a squeeze

A few years ago I lived in a ground floor flat which turned out to be very damp. In the morning there would be slug trails criss-crossing the floor. You had to cross the kitchen to reach the bathroom, and on more than one occasion I felt the wet squidge of a slug beneath my bare toes as I made my way across the floor in the night. A friend once woke up in our spare room with a slug beside her, on the pillow.

Where were they getting in? I wondered… and then I was amazed to catch sight of one entering the kitchen through the tiniest crack beneath the window. As I watched the slimy contortionist squeeze its body through the crack, I realised they could be getting in anywhere.

A slug has no bones or a shell, and can stretch its body to about twenty times its length to squeeze through narrow gaps. This video shows a yellow slug (Limax flavus) squeezing through the tube of a ballpoint pen

Snail 2.0

This squeezy skill is what sets the slug apart from its cousin, the snail. Which came first, do you think? You might reasonably assume that the shelled model is the more advanced. But in fact, slugs evolved from snails. A snail might be able to retreat into its shell to avoid drying out, but by shedding its cumbersome shell a slug can do even better. It squeezes through tiny cracks into dark, damp spaces and waits it out until conditions are wetter and better.

Have you heard of ‘semi-slugs’? Not common in Britain, these are slugs which still have shells on their backs that are too small to retreat inside. One was spotted in Wales a few years ago.

Spotting the difference

One of the world’s largest slugs is found in Britain’s ancient woodlands: the ash black slug (Limax cinereoniger) can reach 25cm long.

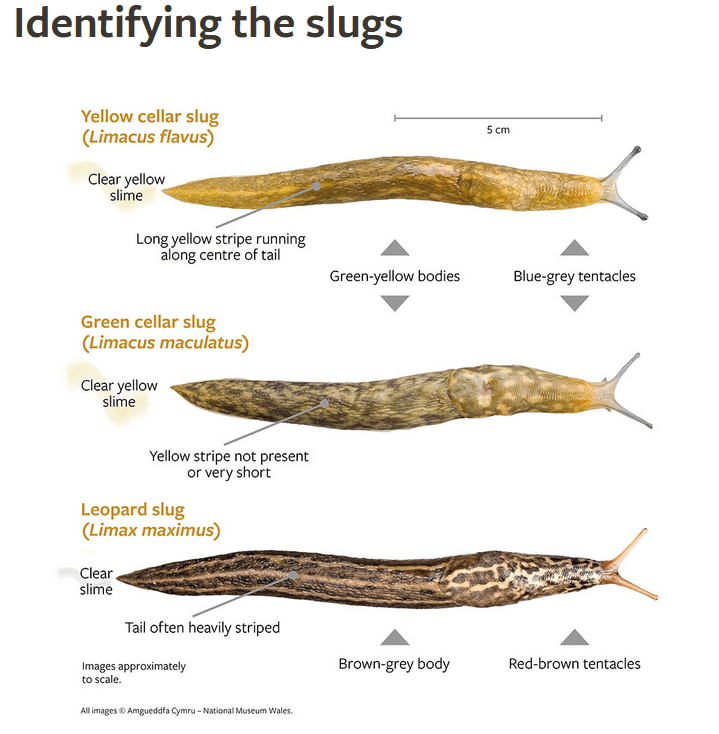

Other species are less easy to identify. When identifying slugs, look for the slug’s right hand side where the breathing pore is. In fact all the action takes place here; it’s also where the slug’s genital opening is, and where they poo from. Some differences in these features can help you identify which slug you’re looking at, so make sure you get a photo of the slug’s right hand side if you want to try and identify it later, as advised in this guide to identifying British slugs.

Other helpful differences you might spot are distinctive markings on the slug’s body, or a difference in colour between the body and the edge of the foot.

The white ghost slug (Selenochlamys ysbryda) is unmistakeable, being unusual in both appearance and behaviour. It was first identified in Wales, lives deep underground and eats earthworms, and is very distinctive with the mantle and breathing hole at the tail end of the body, unlike most other species.

You can help with slug research! Look out for these: the yellow cellar slug (Limacus flavus) and the green cellar slug (Limacus maculatus), and report any to the Cellar Slug Survey. Neither are considered pests as they feed on rotting plant material, but researchers want to find out what impact the newer green cellar slug (seen in Britain since the 1970s) is having on the yellow cellar slug, which has been around much longer.

Let’s talk about slime…

Mucus is produced all over the slug’s body, and a slug amazingly produces two different kinds of slime: one for defence, and one for movement. This is also an identifying feature of slugs, as slime colour differs between species. Cavadino says that if you rub a slug’s body you can see what colour their defensive slime is, and if you put a slug on some white paper you’ll see their movement slime.

…and, of course, let’s talk about slug sex

Slugs are hermaphrodites, like earthworms, so when they mate they both receive sperm.

Some slug mating rituals are incredible. In this extraordinary video of two leopard slugs mating, after an hour of twisting around one another they descend like aerial acrobatic lovers on a rope of slime, then extend their male genitalia which unite in an ethereal orb to exchange sperm.

They lay their eggs somewhere dark and damp. Last month my two year old discovered these eggs in our garden, and the following week there were more in the same place, this time being freshly laid.

The babies hatch out as miniature slugs. Here’s a beautiful BBC Earth video of baby slugs hatching inside a wall.

Give a slug a break

I hope you’ll now come to appreciate the beauty of slugs. But if you still want to keep these loveable slimers out of your garden, here are a few nature-friendly tips. Barriers don’t often seem to work. Slugs can crawl over anything, including egg shells and even razor blades. Copper rings seem to deter slugs in lab tests, but in gardens they just sneak underneath.

There are plenty of other natural approaches though. Get a pond to attract frogs and toads to your garden. Make your garden and street welcoming for hedgehogs. All these animals love a tasty slug. You can also choose plants for your garden which slugs won’t go for: strong smelling or hairy plants for example, or choose what Cavadino calls a sacrificial plant for the slugs to eat, like nasturtiums.

Don’t use slug pellets. Not only is this bad for helpful slugs, but it can poison animals who eat them too. Oh, and move them far enough away so that they don’t just follow their tentacles straight back again – twenty metres or more if you can.

Movie stars

I can’t end this blog without mentioning SLUGS, a silly but entertaining 80s horror film about mutant killer slugs which I would file under ‘so bad it’s good’. Enjoy.

Find out more

- Land and freshwater molllusca of Britain and Europe: facebook group

- Watch Imogen Cavadino’s talk ‘Slimy, Sticky and Unloved: Slugs in Britain’

One thought on “Let’s talk about slugs”